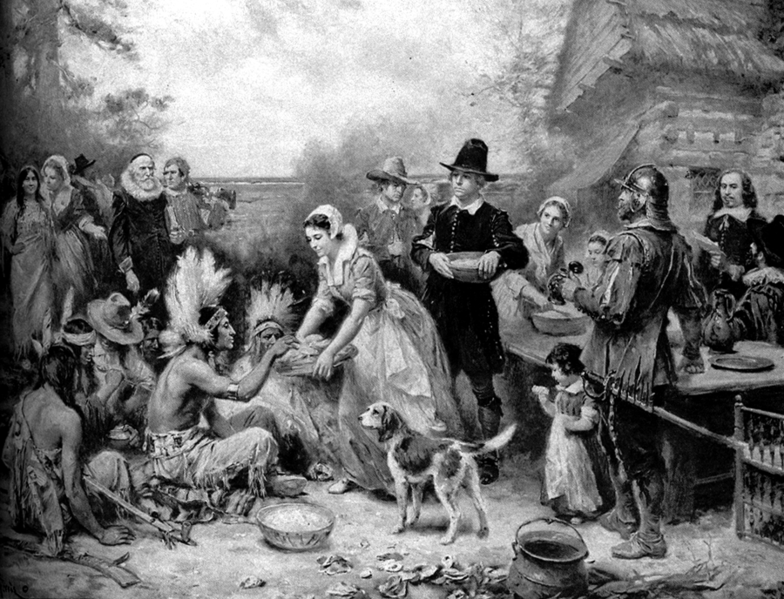

Thanksgiving has become synonymous with family, food and football over the years. But this unassuming American holiday is not without controversy. Schools still teach children that Thanksgiving marks the day that Pilgrims met helpful Indians who gave them food, farming techniques and other strategies to overcome the bitter New England cold. The children color cutouts of happy Pilgrims and happy Indians that ignore the reality that contact between the two marked the beginning of the decimation of millions of Native peoples. To raise awareness about the price indigenous people paid for Thanksgiving, a group called the United American Indians of New England established Thanksgiving as its National Day of Mourning in 1970. The fact that UAINE mourns on this day poses a question to any race-conscious American: Should Thanksgiving be celebrated?

Why Some Natives Celebrate Thanksgiving

The decision to celebrate Thanksgiving divides even Native Americans. Nearly 10 years ago, Jacqueline Keeler wrote a widely circulated editorial about why she, a member of the Dineh Nation and Yankton Dakota Sioux, celebrates the holiday. For one, Keeler views herself as “a very select group of survivors.” The fact that Natives managed to survive mass murder, forced relocation, theft of land and other injustices “with our ability to share and to give intact” gives Keeler hope that healing is possible.

In her essay, Keeler makes it clear that she takes issue with how one-dimensionally Natives are portrayed in commercialized Thanksgiving celebrations. The Thanksgiving she recognizes is a revisionist one. She explains:

“These were not merely ‘friendly Indians.’ They had already experienced European slave traders raiding their villages for a hundred years or so, and they were wary—but it was their way to give freely to those who had nothing. Among many of our peoples, showing that you can give without holding back is the way to earn respect.”

Award-winning author Sherman Alexie, who is Spokane and Coeur d’alene, also celebrates Thanksgiving by recognizing the contributions the Wampanoag people made to the Pilgrims. Asked in a Sadie Magazine interview if he celebrates the holiday, Alexie humorously answered:

“We live up to the spirit of Thanksgiving cuz we invite all of our most desperately lonely white [friends] to come eat with us. We always end up with the recently broken up, the recently divorced, the brokenhearted. From the very beginning, Indians have been taking care of brokenhearted white people. …We just extend that tradition.”

If we’re to follow Keeler and Alexie’s lead, Thanksgiving should be celebrated by highlighting the contributions and sacrifices made by the Wampanoag. All too often Thanksgiving is celebrated from a Eurocentric point of view. Tavares Avant, former president of the Wampanoag tribal council, cited this as an annoyance about the holiday during an ABC interview.

“It’s all glorified that we were the friendly Indians and that’s where it ends,” he said. “I do not like that. It kind of disturbs me that we…celebrate Thanksgiving…based on conquest.”

<

<

Schoolchildren are particularly vulnerable to being taught to celebrate the holiday in this manner. Some schools, however, are making headway in teaching revisionist Thanksgiving lessons. Both teachers and parents can influence

Thanksgiving in School

An anti-racist organization called Understand Prejudice recommends that schools send letters home to parents addressing efforts to teach children about Thanksgiving in a manner that neither demeans nor stereotypes Native Americans. Such lessons will include discussions about why not all families celebrate Thanksgiving and why the representation of Native Americans on Thanksgiving cards and decorations has hurt indigenous peoples. The organization’s goal is to give students accurate information about Native Americans of the past and present while dismantling stereotypes that could lead children to develop racist attitudes later on. “Furthermore,” the organization states, “we want to make sure students understand that being an Indian is not a role, but part of a person’s identity.”

The Understanding Prejudice organization also advises parents to deconstruct stereotypes their children have about Native Americans by gauging what they already know about indigenous peoples. Simple questions such as “What do you know about Native Americans?” and “Where do Native Americans live today?” can reveal a lot. Of course, parents should be prepared to give children information about the questions raised. They can do so by using Internet resources such as the data the U.S. Census Bureau has compiled on Native Americans or reading literature about Native Americans. The fact that National American Indian and Alaskan Native Month is recognized in November means that plenty of information about indigenous peoples is always available around Thanksgiving.

Why Some Natives Don’t Celebrate Thanksgiving

The National Day of Mourning kicked off in 1970 quite unintentionally. That year, a banquet was held by the Commonwealth of Massachusetts to celebrate the 350th anniversary of the Pilgrims’ arrival, according to UAINE. The organizers invited Frank James, a Wampanoag man, to speak at the banquet. Upon reviewing James’ speech—which mentioned European settlers looting the graves of the Wampanoag, taking their wheat and bean supplies and selling them as slaves—banquet organizers gave him another speech to recite. Only, this speech left out the gritty details of the first Thanksgiving, according to UAINE.

Rather than deliver a speech that left out the facts, James and his supporters gathered at Plymouth. There, they observed the first National Day of Mourning. Since then, UAINE has returned to Plymouth each Thanksgiving to protest how the holiday’s been mythologized.

In addition to the misinformation the Thanksgiving holiday has spread about Natives and Pilgrims, some indigenous peoples don’t recognize it because they give thanks year-round. During Thanksgiving 2008, Bobbi Webster of the Oneida Nation told the Wisconsin State Journal that the Oneida have 13 ongoing ceremonies of thanksgiving throughout the year.

Anne Thundercloud of the Ho-Chunk Nation told the journal that her people also give thanks on a continual basis. Accordingly, marking one day of the year to do so clashes with Ho-Chunk tradition to a degree.

“We’re a very spiritual people who are always giving thanks,” she explained. “The concept of setting aside one day for giving thanks doesn’t fit. We think of every day as Thanksgiving.”

Rather than singling out the fourth Thursday of November as a day to give thanks, Thundercloud and her family have incorporated it into the other holidays observed by the Ho-Chunk, the journal reports. They extend Thanksgiving observance until Friday, when they celebrate Ho-Chunk Day, a large gathering for their community.

Wrapping Up

Will you celebrate Thanksgiving this year? If so, ask yourself just what you’re celebrating—family, food, football? Whether you choose to rejoice or mourn on Thanksgiving, initiate discussions about the holiday’s origins by not just focusing on the Pilgrims’ point of view but also on what the day meant for the Wampanoag and what it continues to signify for American Indians today.

This article touched on what is true. People should ask themselves why are they celebrating one day to give thanks. Everday is a thanful day.

Very well done.We must de-educate to educate. This can possibly make education patitable to yoy, ewspcially Native American, Hispanic-American and Afro-American Youth. The truth can set you free, but getting the truth to those who have either accepted the lie or they are afraid of the liar is the issue. This observation is a step in the direction that is needed in educating those turned off by current educational practices and curriculum.